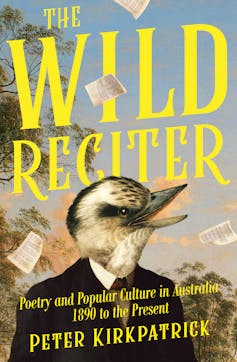

In his latest book, Peter Kirkpatrick retrieves from Australian cultural history the compelling figure of the “wild reciter”, as a reviewer in the 1920s termed amateur elocutionists.

From the late 19th century, men, women and children recited popular verses to audiences who shared in the mass appeal of poetry. Their performances could become histrionic or strident.

Review: The Wild Reciter: Poetry and Popular Culture in Australia, 1890 to the Present (Melbourne University Publishing)

Bush ballads by Henry Lawson and A.B. “Banjo” Paterson, as well as English and American classics and topical verses, formed the repertoire of public speakers, such as the “Tangalooma Tiger” – one of many eccentrics who frequented Sydney’s Domain, drawing large crowds.

Children who learned elocution as a form of self-improvement and social mobility would practise their craft at local events. In 1933, Nancy Turner from Lithgow performed James Elroy Flecker’s War Song of the Saracens at the first City of Sydney Eisteddfod. The Daily Telegraph reported that Turner

recited like a ferocious kitten, and screwed her eyes up tightly when she shouted “We have marched from the Indus to Spain and, by God, we will go there again”, as if she meant it.

“Light-years behind Taylor Swift in terms of high-class showbiz professionalism,” writes Kirkpatrick, “the wild reciter represents poetry’s neglected and – in the best possible sense of the word – vulgar past, offering a perspective that might also speak to its present and future as a demotic art.”

A privileged place

We turn to poetry for many of life’s significant moments. Weddings and funerals remind us that rhyming verse has a privileged place in human communication. The form is freighted with meaning and can express heightened emotion. Achingly earnest or spiritually intense, romantic or maudlin, poetic language affects us, even in popular usage such as greeting cards.

In these instances, we do not always hear “good” poetry. Aesthetic qualities are often ranked second to a poem’s timely message or the personal feelings of the poetic messenger.

George Orwell coined the phrase “good bad poems” in 1942 to describe 19th-century favourites, such as Rudyard Kipling’s If and the boys’ own imperial adventure poem Gunga Din. Orwell called such poems “vulgar”; these days we might call them clichéd (and racist). Yet he observed that they expressed emotions “which nearly every human being can share”.

Orwell also reminded his readers that poems are mnemonic devices. Many older Australians can still remember verses from their schoolrooms. According to historians Martyn Lyons and Lucy Taksa, those brought up around the first world war were a “poetry generation”. Many of those brought up in the aftermath of the second world war can recite verses from the school readers that used to structure their English literature classes.

Being able to recite as well as appreciate poetry was seen as a foundational educational skill, even if children mostly remembered stirring lines such as “the boy stood on the burning deck,” from Felicia Hemans’ Casabianca.

As political commentator Rory Stewart explains in his BBC podcast The Long History of Argument, speaking and arguing well have been seen for millennia as the key to a good education and the building blocks of democracy. Turn of the century experts, such as the American Alfred Ayres – the pen name of Thomas Embly Osmun (1826–1902) – advocated a modern style of verse performance.

Late Victorian elocution, Ayres wrote, was characterised by

orotunds, sostenutos, whispers and half-whispers, monotones, basilar tones and guttural tones, high pitches, middle pitches and low pitches, gentle tones, reverent tones, and all the rest of that old trumpery that has made many a noisy, stilted reader, but never an intelligent, agreeable one.

The old school of elocution, he argued, produced “readers occupied with the sound of their own voices”. Modern elocution, by contrast, sought to clarify “the art of speaking words in an intelligent, forcible, and agreeable manner”.

Appreciating the art of rhetoric may become ever more important in our “post-truth” world. In the age of artificial intelligence, literature professors like me are considering a return to oral assessments to verify our university students have read and understood the course readings, not just regurgitated a ChatGPT summary.

Songs and mass media

Kirkpatrick enjoys disrupting assumptions about high and low culture. He begins his book with Taylor Swift, whose 2024 album The Tortured Poets Department and subsequent world tour spawned events, media articles and academic conferences. He ends by speculating about who might be appointed as Australia’s first Poet Laureate, suggesting indie rock singers such as Nick Cave and Paul Kelly, or First Nations rapper The Kid Laroi, have a stronger hold on the public imagination than literary poets.

He has a soft spot for Evelyn Araluen’s bestselling collection Dropbear, but wonders how a First Nations poet would feel about a position intended to amplify the literature of the colonial state.

The most sustained focus on women’s writing in The Wild Reciter is reserved for Lesbia Harford’s “mortal poems”. Like the colonial Irish-Australian poet Eliza Hamilton Dunlop, Harford set and sang her poems to Irish tunes. Whether Harford meant her poems to be sung by others remains an elusive question. But Kirkpatrick rightly notes that “we now hold song lyrics in our heads in the way that Harford’s generation held poems”.

Recurring poetic motifs, such as horses, allow Kirkpatrick to show how bush ballads contributed to emerging forms of 20th-century entertainment. Popular Australian themes would have a global influence, as modern technologies brought imagined communities together via radio, cinema and popular music. Kirkpatrick links Paterson’s The Man from Snowy River (1890) to Buffalo Bill and touring Wild West shows, and later to the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games opening ceremony.

Identifying how poetry has interacted with different media challenges the common assumption that poetry is formal or stuffy: something confined to university study and highbrow poetry readings. Kirkpatrick argues, for example, that Kenneth Slessor’s appreciation of recorded music influenced his verse, as did his work as a cinema critic for the popular magazine Smith’s Weekly.

Radio programs provided opportunities for Ronald McCuiag’s light verse to reach audiences from the 1940s to the 1960s. John Laws, characterised by Bob Ellis as “the worst poet in the whole history of the entire universe”, was certainly advantaged by his long talkback radio career, which ensured a market for his five collections of poetry.

Kirkpatrick is adept at waspish summaries of bad poetry. Celebrity brought attention to Clive James’ poems – more, perhaps, than they deserved. “It’s not simply the earnestness of so many of his later poems that disables them,” writes Kirkpatrick: “the humorous ones are just as likely to disappoint.”

Popular poetry that Kirkpatrick doesn’t much care for receives little attention, and sometimes unkind assessment. He does not find Dorothy Porter’s The Monkey’s Mask (1994), a lesbian detective novel in verse, nearly as innovative as Porter or her admiring academic critics have claimed.

More than “any other kind of present-day reading or recitation”, Kirkpatrick enjoys slam poetry performances, but he finds them hard to critique. He views them as highly personal and ephemeral, based on his experience of the Bankstown Poetry Slam and the Australian Poetry Slam. His assessment mirrors cultural criticism of rap: “Slam comes from America and its missionary zeal talks with an American accent.”

Considering a contemporary Australian writer like Maxine Beneba Clarke might have revealed more complex oral poetry lineages here. Clarke’s poetry shifts confidently across performance and print; her work with schools demonstrates the ongoing vitality of poetry, and the importance of poetic education, for diverse youth communities.

Clarke’s poem Tik Tok Dance shows that the relationship between poetry and new media technologies, which Kirkpatrick traces impressively throughout the book, is constantly evolving.

“Changing the wor(l)d, verse by verse!” is the evocative catchline for the youth section of the Bankstown Poetry Slam. In February 2025, a Grand Slam billed as “Australia’s largest live poetry event” and starring the Irish–Indian “Instapoet” Nikita Gill was held at the Sydney Opera House, the heart of high culture.

Kirkpatrick is a poet and critic whose deep knowledge of poetry, literary magazines and media cultures is evident throughout. Each chapter in The Wild Reciter focuses on a different instance of popular poetry. Academic readers will recognise some chapters from their earlier publication in various books and journals.

Those professional critics might find the thin veil of scholarship in the book frustrating, but its entertaining style does not pretend to high theory, or even to much close reading. The Wild Reciter is a pacey, provocative romp through Australian literary history. Kirkpatrick enjoys a bon mot and his writing is amusing and sharp.

The figure of the public orator gets lost in some chapters – one concerns the Railroad, a magazine published by the Australian Railways Union. But it is a pleasure when the wild reciter returns in ever-new guises to thread together the multifarious parts of this enjoyable book, which returns poetry to the Australian people.