JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — In his viral video “Who I Smoke,” Jacksonville rapper Spinabenz claims credit for no fewer than six murders.

The crimes are real. But are his lyrics just violent fiction -- or an admission of guilt?

It’s a question at the heart of a new movement to shield rap lyrics from being used in criminal cases. And it’s something that could have direct impact in Jacksonville, where prosecutors frequently use rhymes as evidence of crimes.

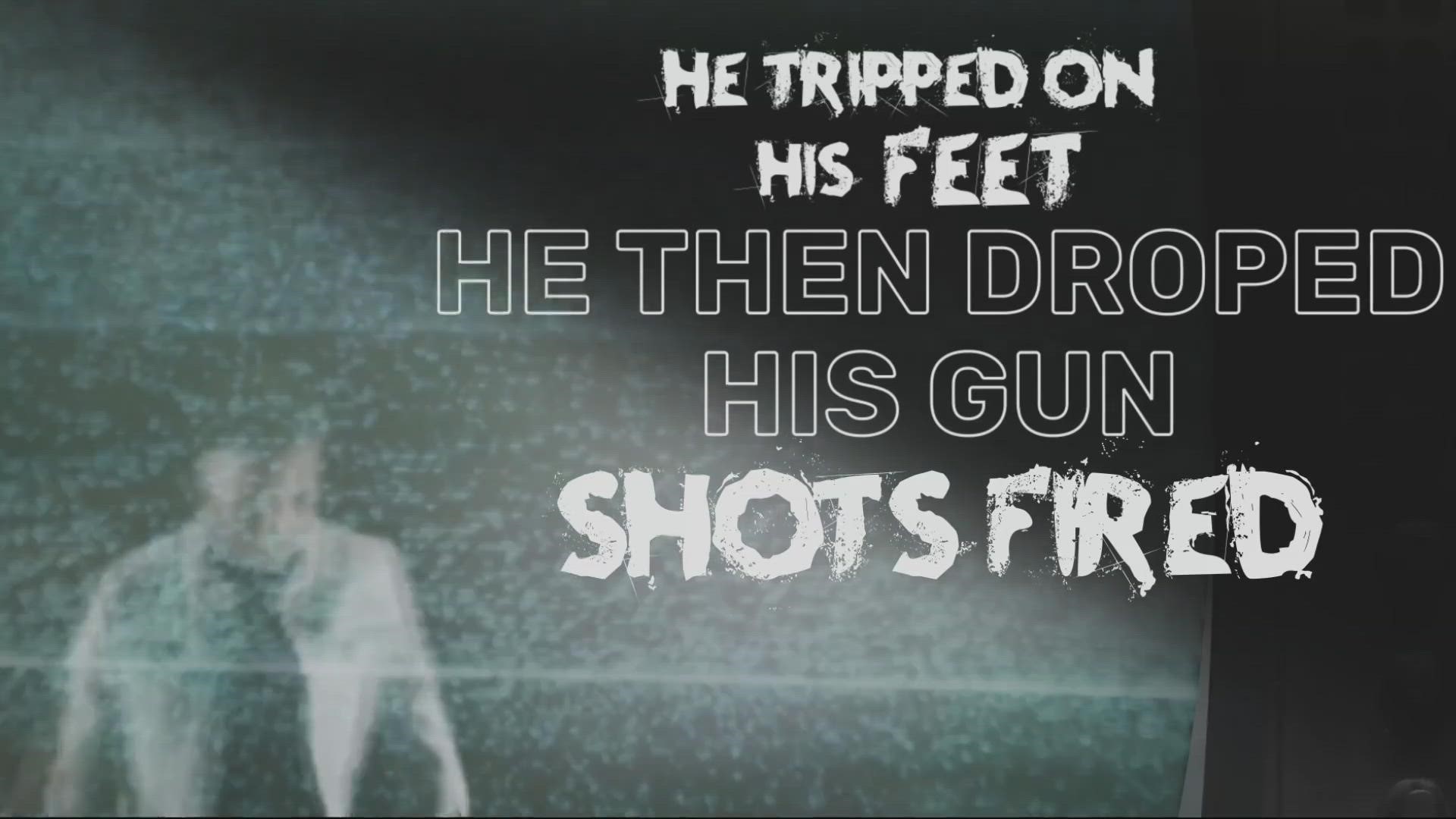

Spinabenz, whose real name is Noah Williams, isn’t accused of murder. But his lyrics were introduced at his recent trial for felony gun possession. Prosecutors played “Who I Smoke” at his bond hearing to show him as a threat to the community. And at trial, they claimed the lyrics his song to “My Glock” mirrored an actual gun purchase.

Williams pleaded not guilty and was acquitted. But he’s just one of several local defendants who’ve had their songs and videos played for a jury -- a practice his attorneys say is a "trend," particularly Florida.

“Just because there's a song by Bob Marley that says 'I Shot the Sheriff,' doesn't mean he actually went out and shot the sheriff,” observes attorney David Bigney.

“And Johnny Cash never spent any time in Folsom Prison, and he never shot a man outside Reno,” chimes in Bigney’s co-counsel Dan Eckert.

The issue gets more complicated when there is an actual dead body, however.

In the case of rapper Ksoo, whose real name is Hakeem Robinson, the state has identified more than a dozen videos that it may introduce as evidence at his murder trial. In one, called “Back to Back,” he raps about killing people “back to back,” specifically naming “Bibby” -- 16-year-old Adrian Gainer -- who Robinson is charged with murdering.

“Do the F****** Bibby dance. Grabbing all these souls, I only got 2 F****** hands.”

He name-drops Bibby in other songs as well, including “Ksoo Bitch.”

“Ksoo Bitch, you know we smoke little Bibby b*tch”

Rapper Y&R Mookey, whose real name is Tyler Jackson, was convicted last year of felony firearms possession based in part on videos showing what appeared to be real weapons and drugs.

“The state is prosecuting my music videos, and not who I am person,” Jackson complained to Circuit Judge Meredith Charbula.

“I watched the music videos, and I have to say that I’m appalled at the content,” Charbula responded, before sentencing him to 10 years in prison. (His conviction is being appealed.)

Rap videos also figured prominently in the 2018 trial of two teens accused of murdering toddler Aiden McClendon. Prosecutors said the lyrics memorialized actual crimes committed by gangs affiliated with Henry Hayes and Kquame Richardson, including drive bys and retaliatory shootings.

“It’s called drill music. They talk about what they have done. They talk about what they’re going to do,” then prosecutor (now Judge) London Kite told jurors.

“These are not songs; these are not raps — these are admissions,” Chief Assistant State Attorney L.E. Hutton told jurors.

There’s no question that social media and music videos have helped law enforcement track gang loyalties and burgeoning beefs. In some cases, videos showing guns have been used to obtain search warrants, which turned up actual weapons or other criminal activity. Videos are also used to prove gang affiliations, which can enhance criminal penalties.

So key is the connection between music videos and criminal enforcement, the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office dubbed a 2019 dragnet “Operation Rap Up.”

But there is a growing movement to limit or even prohibit using a rapper’s artistic output as evidence. A bill introduced in New York would limit prosecutors’ use of rap music or videos, dictating when and how a performers “creative output” can be referenced in court.

In October, California passed the Decriminalizing Artistic Expression Act, which included online signing ceremony featuring Killer Mike, Too Short, Meek Mill, Tyga, Saweetie, E-40 and Ty Dolla Sign.

And in Atlanta, U.S. Rep. Hank Johnson has introduced federal legislation that would set standards limiting when an artist’s “creative expression” can be used as evidence.

“When it's known that you are a rapper, that designation conjures up perceptions of gang violence, drug dealing, rape, murder,” he told First Coast News. “There's a need for this legislation, because rap music is the only genre of music that, that we know that subjects its creators to criminal liability.”

The push to limit or prohibit rap as evidence is based in part on research about its use and impact. University of Georgia Professor Andrea Dennis found 500 cases where rap was used as evidence at trial, including some involving the death penalty. Rap is the only art form used consistently at criminal trials, she found, and it’s not without prejudice. Numerous studies have shown the genre evokes stereotypes and racial bias, its lyrics far more likely to be associated with criminality than similar lyrics in a country song.

“Whether used as autobiographical confession, evidence of state of mind, evidence of bad character, or as a threat, rap is the only fictional music genre used in this way,” Dennis said in an interview with UGAToday. “And the use of rap lyrics as criminal evidence is part of a larger and longer history of using racial epithets, racial imagery, stereotypes and narratives to criminalize and convict Black and Latino men.”

Eckert and Bigney, who also represented Florida rapper 9lokknine (Glock 9) at his murder trial, acknowledge in some cases, performers' stage personas and lyrical content are a legal liability. Asked if they ever urge clients not to rap about actual crimes, Eckert smiles. “We can't say we've never said it.” But both insist the lyrics, even violent ones, are an essential part of a lucrative business model.

“You are essentially asking them to not make a living anymore, or find another way to make a living that is isn't in rap,” says Bigney. “These labels are handing over millions of dollars to some of these artists just a signing bonuses to do exactly what they've been done that what they're doing. And so from that perspective, it's not only their their target audience, but they're trying to keep their label happy, because their label is the one that's paying their bills."

First Coast News reached out to the State Attorney’s Office. They declined an interview request, but sent this statement:

“In Florida, appellate courts have ruled that rap lyrics can be offered by the State to establish both motive and identity of the defendant who committed the charged crime. When introduced at trial, rap lyrics can be evidence of the defendant celebrating murders they have committed and, in others, foretell of those intended.”

In this regard, local prosecutors are in lockstep with their counterparts in Atlanta, where the rap scene is more prominent but no less violent. In an Aug. 5 indictment, District Attorney Fani Willis charged Atlanta rapper Young Thug and more than a dozen others with a variety of gang related drug and firearm charges, in part based on their lyrical content.

When asked about the practice, she staunchly defended it. “If you decide to admit your crimes over a beat, I’m going to use it,” she said at a press conference. “I’m going to continue to do that. People can continue to be angry about it. I have some legal advice: Don’t confess to crimes on rap lyrics if you don’t want them used — or at least get out of my county.”