As Covid-19 ravaged Ecuador’s largest city, Guayaquil, in the first months of the pandemic and spread through the rest of the country, smaller and more isolated communities were often the safest but forced to look to themselves to educate their children.

As the photographer Johis Alarcón discovered on her visits to the indigenous village of San Clemente in the Andean highlands and the African-Ecuadorian hamlet of Playa de Oro in the coastal rainforest bordering Colombia, a renewed sense of community grew.

The pandemic has presented as an opportunity to re-establish community education and to restore previously abandoned infrastructure

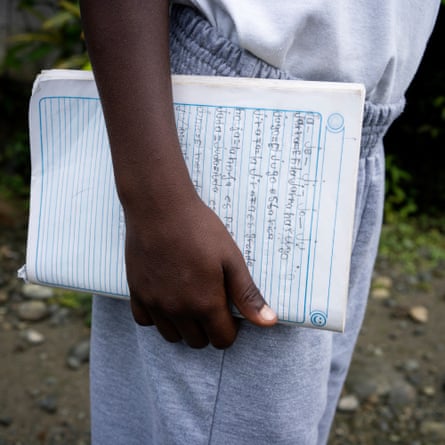

Isolated populations were hit hardest by the closure of schools during the pandemic, whichaffected 4.6 million students, of whom two-thirds do not have internet access, according to Unicef. The lack of smartphones, internet connectivity and a drop in income for their parents became a major obstacle to their continued schooling.

The response was to relaunch community schools that promote their cultural identity and language, the protection of the local environment and whose teachers are also part of the community. Indigenous people make up 7% of the country’s population and African-Ecuadorians about 8%.

Patricio Bermeo school, San Clemente

Teachers and students of Patricio Bermeo school in San Clemente in the northern highlands. Before the pandemic, the school had 45 students. Now it has more the 60 because some families came back to their community during the lockdown. They prefer their children to study at community schools to avoid the risk of infection in urban areas

Two Karanki indigenous girls study together

San Clemente is an indigenous Karanki community in the foothills of the Imbabura mountains. The site is one of four Unesco geoparks in Latin America and the Caribbean, selected for their geographical and cultural wealth.

Top left, Sayana Cuasque’s mother combs her hair before school. The uniform is the traditional Karanki dress that includes a handmade embroidery blouse, skirt, gold earrings, necklace and traditional shoes called ‘alpargatas’. Right, a class at San Clemente. Top right, a class at San Clemente. Above, Katerine Pupiales, 20, and Marisol Pupiales,27, two community teachers, poses for a portrait in their home. Marisol volunteers at San Clemente school, teaching the indigenous Kichwa language

Returning from the city, several families created a community school parallel to the public school with the aim of strengthening the Kichwa language and identity among the children, recounts Alarcón, who comes from the capital Quito, about a three-hour drive away. Young volunteers teach music and theatre and skills such as cooking, basic English and adventure tourism with a view to cater for tourists looking for a community-based experience.

Katherine Pupiles is a community teacher and physiology student at Quito University. She returned to the San Clemente community when the pandemic began

“The children should be free to learn,” said Marisol Pupiales, 27, a mother who teaches the Kichwa language as a volunteer in the school. She is one of many parents who have become more involved in their children’s education.

Playa de Oro community school

Children at the Playa de Oro community school.

Far more remote, Playa de Oro, a tiny African-Ecuadorian community of around 80 families, scarcely had internet to begin with. The public school teachers have not returned to the hamlet since the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020. Access is by river and the local economy relies on artisanal gold mining, logging and agriculture.

Its isolation has also meant not a single case of Covid-19. Three young women, Kerly Venazca Ayoví, 26, Morení Arroyo, 23, and María Teresa Caicedo, 23, took charge of the community school, earning a minimum monthly wage of $150. Parents clubbed together to install internet antennas and buy mobile phones so their children could continue with their classes.

Juleixy Medina, 12, poses for a portrait in her schoolyard in Playa de Oro. She wants to be a doctor, she was in her last year of school when on-site classes were cancelled because of the Covid-19 pandemic in Ecuador. Juleixy attends classes at the community school and is part of the marimba dance group led by the community’s youth

“We committed ourselves because of the love we have for the community,” said Caicedo, who gave the classes while pregnant with her daughter Noa. The first woman in her family to go to university, she was in her final year studying social work when the pandemic struck.

“I want to improve the education of my daughter,” she said. Other mothers volunteered to give extra classes for the 50 primary school students.

Top, a group of children sings an arrullo, a type of African-Ecuadorian song, during class. Above, Xiomara Jimenez, 11, Analía Peralta, 11, and Luis Medina are do their homework. They have group meetings to help each other with difficulties

The classes from 8.30am to midday include maths and language but also reinforce African-Ecuadorian identity with traditional songs called arrullos and classes in the traditional marimba dance.

Danny Valencia, Yuleixy Medina and Rafael Arroyo participate in a study group with the help of their aunt Zugey, a community leader who helps children with their homework

The children already know what they want to be when they grow up, said Alarcón. Choices range from doctors, chefs, soldiers, actors, musicians, dancers, footballers and even one sculptor.

A poster of the alphabet and multiplication tables in the living room of the Ayoví family in Playa de Oro. Parents have to create different learning resources for their children

“In order to fulfil their dreams they have to leave their home. They leave their families and the communities become fragile,” she said.

But the community school experience has meant many now want to return home one day, bringing their skills with them.