- India

- International

From samosas to Fado music, an online initiative is celebrating everything creole in India

In an attempt to celebrate the remarkable cultural interchanges in creolised cultures, through discussions and performances, Ananya Jahanara Kabir and Ari Gautier have launched an online initiative, ‘Le thinnai kreyol’.

In an attempt to celebrate these remarkable interchanges in creolised cultures, through discussions and performances, Ananya Jahanara Kabir and Ari Gautier have launched an online initiative, ‘Le thinnai kreyol’. (Source: Wikimedia Commons/ edited by Gargi Singh)

In an attempt to celebrate these remarkable interchanges in creolised cultures, through discussions and performances, Ananya Jahanara Kabir and Ari Gautier have launched an online initiative, ‘Le thinnai kreyol’. (Source: Wikimedia Commons/ edited by Gargi Singh)

As Ananya Jahanara Kabir begins the live session on Facebook titled ‘Thinnai kucini’ , she holds up a plate of crisp, golden croquettes, a popular snack in Bengal. “The original croquette as made by the Dutch has Bechamel sauce, but who could make that sitting in the middle of the Hugli delta? So we put in spices, ginger, garlic, and then we coat it with bread crumbs which is a technique that Bengal learnt from the Portuguese,” says Kabir about the dish which is derived from the French word, ‘croquer’ (to crunch).

Kabir is joined by writer Ari Gautier, a Franco-Tamilian from Pondicherry who is currently based in Oslo. Gautier too had prepared a dish to discuss in the virtual event. The ‘Rougaille Mattikallu’ he displayed is a combination of the Pondicherry dish, Mattikallu (freshwater mussels) and the spicy tomato based sauce popularly eaten in Mauritius and the Reunion island called Rougaille. The Rougaille is a product of the 19th century when indentured labourers from Pondicherry left for the islands, and the word in itself is derived from the Tamil, ‘urukai’, meaning pickles.

In this 90-minute long live session, Kabir and Gautier discussed food items that have a unique past of encounters between European and non-European cultures, or what is known as creole. In an attempt to celebrate these remarkable interchanges through discussions and performances, Kabir and Gautier have launched an online initiative, ‘Le thinnai kreyol’.

The Rougaille is a product of the 19th century when indentured labourers from Pondicherry left for the islands, and the word in itself is derived from the Tamil, ‘urukai’, meaning pickles. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Rougaille is a product of the 19th century when indentured labourers from Pondicherry left for the islands, and the word in itself is derived from the Tamil, ‘urukai’, meaning pickles. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

“Global modernity is shaped by creolisation: unexpected encounters that gave rise to cross-cultural transfusion, negotiation, compromise, and unpredictable innovation,” writes Kabir in an email interview with Indianexpress.com. Kabir who is a professor of English at King’s College, London but is based in Manchester, has done extensive research on creolised cultures. “The unequal power relations and violence catalysed through slavery, colonialism, and trade did not kill culture; rather, creolised music, dance, food, clothes, architecture, and language stubbornly emerged. Creolised cultural forms resist power and hegemony. They flourish right under the nose of power,” she adds.

Creolisation: A history

The process of creolisation was in the beginning essentially a process of language creation. Creole languages developed out of the necessity to communicate between two different ethnic, socio-cultural groups. Majority of these language systems date back to the 16th and 17th centuries when European colonial powers traversed along the Atlantic and Indian ocean.

The term creole in itself, has a fascinating etymology that draws in from multiple linguistic roots. Linguist John A. Holm in his book, ‘An introduction to Pidgins and Creoles’, explains that creole is born out of the “Latin ‘creare’ to create which became Portuguese criar, ‘to raise’.” Consequently, the word Crialo came to mean an African slave born in the New World. “The word finally came to refer to the customs and speech of Africans and Europeans born in the New World,” writes Holm. “It was later borrowed as Spanish ‘criollo’, French ‘creole’, Dutch ‘creools’, and English ‘creole’,” he adds.

But as Kabir and Gautier explain, the ‘c’ in creole as used by the Europeans is replaced by ‘k’ among the languages in the island countries of the Atlantic and Indian oceans.

It is also important to note that for the longest time, the languages and cultures born out of this process of creolisation were looked down upon, considered to be corruptions of the ‘higher’, usually European languages. Holm explains that it is only from the 19th century, that linguists have realised that creoles are not inferior forms of European languages, but rather new language systems in themselves. At present, there are close to 1,500 documented creolised languages around the world.

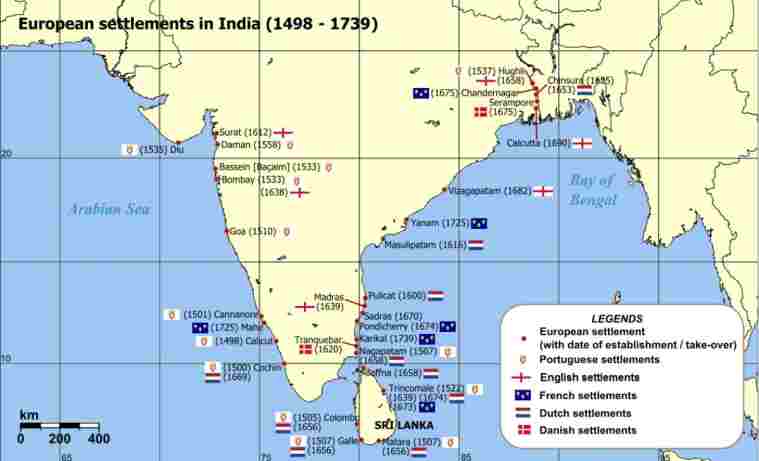

But over time, the word ‘creole’ has also come to be associated with food, music, dance and a lot more that was a product of these unexpected encounters between two ethnic groups. In India, the process of creolisation can be traced back to the time when the Portuguese landed in the west coast of India in the 15th century. Over the next few centuries, colonial interactions with the French, Dutch, and the English produced astounding cultural exchanges.

European settlements in India in the 15th-18th centuries. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

European settlements in India in the 15th-18th centuries. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

But cultural encounters were not limited to those with European powers. Kabir and Gautier explain that even though Creole as a historical concept is pinned down to the seaborne activities of European colonisation, theoretically it can be used to understand other cultural contacts as well, like that with the Turks and Arabs. “We will, over time, showcase and discuss the inter-cultural encounters of pre-colonial India as well. In fact, it would be interesting to extend the usage of the term creolisation and look at how it played out in case of the Cholas in South East Asia,” they say.

A celebration of creolisation: ‘Le thinnai Kreyol’

Kabir and Gautier launched ‘Le thinnnai kreyol’ on May 26. “It was a project born out of lockdown frustration and the need to connect,” she says. However, as they explain there are two prime objectives of their initiative. First, is to revisit and celebrate these disappearing stories of remarkable creolised cultural inventions. Secondly, as Gautier explains, “it is a space of resistance against the effort to impose a monolithic culture.” “This is most important in the socio-political scenario of our times. We want to emphasise the plurality inherent in India,” he says.

“The name ‘Le thinnai kreyol’ conveys our politics,” they say. ‘Thinnai’ is the Tamil word for a raised platform or veranda in front of a house. It has multiple uses as a gathering place for family, neighbours, strangers, and travellers. Le is French for ‘the’. “The combination ‘le’ + ‘thinnai’ mirrors wider cultural transformations that Pondicherry historically enabled,” says Gautier. Indeed, ‘Le Thinnai’ is the title of his second novel, which narrates precisely those transformations through the literary device of a thinnai where people and their stories gather. Gautier’s concept of the thinnai came together with Kabir’s academic research on creolisation to create le thinnai kreyol. Further, they explain that by using the form ‘kreyol’ (rather than ‘kreol’) aligns the movement to its usage in islands such as Mauritius and Reunion, which share the Western Indian Ocean space with India.

In the past couple of months, Le thinnai kreyol has hosted several events in the digital spaces that have allowed artistes, intellectuals, entrepreneurs to discuss, debate and perform.

“One kind of event we host is what we call thinnai katcheri sessions: with musicians, dancers, writers and scholars. Katcheri is the Tamil word for concert and the Bangla word for legal assembly. Both come from the same Persian word for court,” says Kabir. The first katcheri was on the theme of ‘Rhythms of remembering: Pondicherry meets Goa’. They hosted Sonia Shirsat, the celebrated Fado singer from Goa, and Prabhu Edouard, Pondicherrian percussionist resident in Paris. The event highlighted the commonalities in their experiences as inheritors of Portuguese India and French India and how this heritage shapes their musical journeys and artistic choices.

The first katcheri was on the theme of ‘Rhythms of remembering: Pondicherry meets Goa’. They hosted Sonia Shirsat, the celebrated Fado singer from Goa, and Prabhu Edouard, Pondicherrian percussionist resident in Paris. (Source: Screengrab of the video from the official Facebook page of Le thinnai Kreyol)

The first katcheri was on the theme of ‘Rhythms of remembering: Pondicherry meets Goa’. They hosted Sonia Shirsat, the celebrated Fado singer from Goa, and Prabhu Edouard, Pondicherrian percussionist resident in Paris. (Source: Screengrab of the video from the official Facebook page of Le thinnai Kreyol)

More recently the ‘thinnai kucini’ was a celebration of food heritage. “‘Kucini’ is the Tamil word used to describe kitchen in Pondicherry, and is derived from a Portuguese word ‘cozinha’. The same word is used in the Konkan coast as well,” says Gautier in the Facebook event.

The platform also plans on putting together other events such as thinnai beats with DJ performances and thinnai matinees for streaming films. “Of course, we always have our thinnai addas, which we simply love as a relaxed and completely improvised space,” says Kabir.

But creolisation in India is far from being a uniform process. Given the interactions with diverse groups of outsiders, how does one draw commonalities and bring them together in the same platform? “Indeed it is a paradox that we should want to bring under one umbrella, a word and concept that resists standardisation,” agrees Kabir. However, they explain that even when creolisation happened differently in case of different cultural encounters, there is a historical similarity that connects these experiences.

“We propose describing ourselves as assembling ‘an archipelago of fragments’,” explains Kabir. She says the story of the samosa best exemplifies this. Food historians believe that the concept of the samosa could have circulated either through the sea routes between the Arabic peninsula, East Africa and the Western Indian ocean, or it could have come through land routes as well. The samosa then started travelling further afield with people who left India in different diasporas. Thereby versions of the samosas developed in the western Indian islands like Mauritius and Seychelles. Other versions developed in Southeast Asia, in the Caribbean islands, in Cape Verde via the Portuguese who took them from Goa, and of course in Britain brought through migration of South Asians before and after the Partition. “I see the samosa as a creolised product, but it has many different histories of creolisation that converge in it,” says Kabir.

Apr 19: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05